Art

Overview: A Spectacle

In the Spring of 2016, at the freshly opened SFMoMa, patrons gathered around a pair of spectacles thoughtfully placed against the wall. Some took pictures, others discussed, still others contemplated the meaning of the object. An abstract expressionist once said that the intention of his work was to remove all content and all context so that a viewer would be left only to contemplate herself looking. Perhaps the spectacles were placed with the intention of linking the philosophies and intentions of abstract expressionists with the philosophies and intentions of ready-made art made famous by Duchamp.

The reality, though, is that two teenagers, frustrated with what they thought was silly and pretentious art, placed the spectacles on the ground as a prank. The visitors clearly found value and meaning in the spectacles none-the-less, and art critics could no doubt discuss the impromptu exhibit within the context of other art movements.

Notably, the context provided by the museum provoked the visitors to interpret meaning. Outside of the Museum knowledge is an objective entity that science and mathematics acquire incrementally. Inside the Museum the viewer hermeneutically synthesizes the tradition and context with personal experience in order to build knowledge.

This scene of misunderstanding, nefarious intention, and aesthetic insight force us to ask the question, “How does an artist know?” And, perhaps even more interesting, “How does the viewer/listener/reader of art know?”

ART and the WAYS OF KNOWING

Language:

Isadora Duncan, who was instrumental in developing modern dance in the early twentieth century once said, after being asked about the meaning of her choreography, “If I could tell you, the meaning, I wouldn’t have to dance it!” Considering Duncan’s statement, Language is a symbolic system and the iconography of art also functions as a symbolic symbol. A sense of Aesthetics has evolved in cultures around the world and each creates its own visual or auditory vocabulary. Dewey emphasized this point when he wrote about how “the language of art has to be acquired”.

Additionally, language plays a role in how we define the word “art”. Wittgenstein would argue that there couldn’t be a set definition of art, but that there will be many elements and that bare a familiar resemblance to each other. Art has been defined as “imitation” by Plato, “purposiveness without a purpose” by Kant and “Embodied meaning” by Danto with innumerable definitions between. Dickie’s institutional theory, that art is defined by the art world could be easily compared to Wittgenstein’s idea of linguistic communities.

Emotion

The emotive theory of art, most notably articulated by Tolstoy in his essay “What is Art?”, claims that art can be defined as the expression of emotion. He claims that the highest form of art is that which can communicate and infect the viewer (or listener, or reader) with the emotions of the artist who created it. For Tolstoy the artist would need to conjure up intense emotions and let spill out onto the art work. In this case emotion is both a part of the act of creation and a part of the viewer’s experience. Other aestheticians, like R.G. Collingwood claim that great art is more an exploration of emotion than its communication. For him, a work of art is part of how the artist comes to understand emotion. This, in turn, helps the viewer explore her/his emotions as well. The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge seemed to agree centuries before by claiming that we will know a man for a poet by the fact that he makes us poets.

Reason

Ancient Greek artists, and later Renaissance artists, loved symmetry and purposeful mathematical ratios. This attempt to create beauty from axioms illustrates the ambition of some artists to derive the principles of beauty through reason. By using the Fibonacci sequence, which converges on the irrational number Phi, Renaissance artist arrived at a golden ratio and attempted to produce works of beauty through mathematical reasoning. Likewise, nearly a millennium earlier, Pythagoras and the cult that succeeded him used deductive reasoning to articulate a harmonic sequence and laid the foundations for our understanding of music.

On the other hand, there are many philosophies of art around the globe that consider artistic expression a path to explore elements of the human experience that lie categorically outside the scope of reason. Zen Buddhist gardens, the choreography of Isadora Duncan, and the paintings of Edward Hopper are good examples of artwork that contains a message beyond the scope of reason.

Sense Perception

Art is experienced through the senses, but we all experience sensory stimulus differently. Color, for example, provides meaning in every culture. The redness of a strawberry, for example, provides meaning that the fruit is ripe. But we all experience color differently; in obvious ways like colorblindness, and in less obvious ways like those revealed in the #thedress internet phenomenon. (in the arts that rely more on auditory sense perception you can take the Yani/Laurel as a parallel example)

Additionally, the ways different cultures experience colors differently matters.The Himba, a Namibian tribe, can more quickly, and with greater accuracy pick our variations in the color green, for example.

The color blue in 15th century Europe would have a much different emotional effect than it would for a modern European. In the 15th century the color would be striking note simply because of its depth or beauty, but because the expense of the pigment would be well known and its relationship with the Virgin Mary would inspire reverence. Today there are few, if any, colors more common.

In most cultures the sense of sight and sound are supreme in the arts, but there are notable exceptions like the Japanese Tea Ceremony or Ethiopian Coffee Ceremony which both play to our sense of taste and smell as well.

Shōrin-zu byōbu

Imagination

Much Japanese art, specifically poetry and ink drawings, is more suggestive in meaning than explicit. It forces the viewer to imply meaning through one’s own imagination. This is also the goal of some abstract expressionism in the western culture: to leverage the viewers imagination in constructing meaning.

Of course creativity and imagination also apply to the construction of art. TS Eliot’s well known essay, “Tradition and the Individual Talent” outlines the tension between individual creativity and imaginative force and the traditions and shared cultural vocabulary that participate in the genesis of original art.

Intuition

Freud once explained that the artist “is urged on by instinctual needs he longs to attain in honor, power, riches, fame, and the love of women; but he lacks the means of achieving these gratifications.” Freud is classically heteronormative and misogynistic in that statement, but the role of instinct does play a significant role in both the creation and the experience of art. The artist intuitively creates, and the perceptor intuitively perceives.

Jackson Pollock once responded to a question about abandoning the representation of nature in his work by saying, “I am nature,” which emphasized the role that instinct played in the creation of his work.

Additionally, the experience of perceiving art often relies on instinct. Our first and instinctual reaction to an artwork often plays an important role in our appreciation of a work. A study by Mehr and Singh showed that people can distinguish between celebratory music and remorseful music from foreign cultures reliably, and so we must have an instinctual understanding of the connections between certain sensory experiences and emotion.

Memory

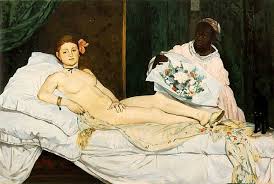

Olympia by Manet

Manet’s painting “Olympia” caused a lot of anger and laughter when it was first displayed in Paris in 1865. For people ignorant of the history of western art, it might be difficult to understand why. For those initiated in this history, though, the painting was clearly referencing the shared memory of Titian’s painting “The Venus of Urbino” with notable divergence. One of these divergences is his use of Victorine Meurent as the model for Olympia, a well known prostitute. The painting plays with different levels of shared memory from the canon of western art to the community of Paris, to the individual with our own visual experiences and associations.

Faith

From Catholicism in Europe to Shintoism in Japan and to Hinduism in India, art traditions often find a meaningful link in the ability of art to link to the sacred and the profane; to help connect the terrestrial world with the spiritual world. In some cases, like Shintoism, the performance of art, symbolized in Ane-no-usume’s music and dance, creates the world as we know it. The anthropologist Steven J. Lansing claimed that, “For the Balinese… The arts provide a way to understand and experience the divine essence”. The same could also be said for Baroque art in Europe or the Medieval Mystery Plays.

Faith also plays a role in the destruction of art as in all iconoclastic movements from the Nike Riots, to Calvinism, and the destruction of artifacts by ISIS today. The monasteries in England were once so plentiful that it would be impossible to stand more than a thirty minute walk from one. They were seen as a connection between the domain of God and the terrestrial world; a key touch point for the sacred to connect with the profane. But Henry VIII’s move toward protestantism and the closing of these monasteries and the white washing or destruction of the artwork was executed under the philosophy that they distracted from truth faith rather than aided it.

Get Lesson Plans

For Teachers looking for Lesson Plan Ideas